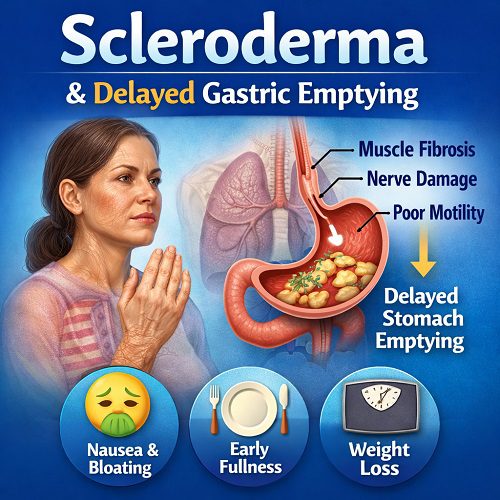

Scleroderma is a chronic autoimmune connective tissue disease characterized by fibrosis (hardening), vascular abnormalities, and immune system dysregulation. While it is often recognized for its visible skin changes, scleroderma can affect multiple internal organs—including the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Among the most impactful gastrointestinal complications is delayed gastric emptying, also known as gastroparesis. This condition can significantly impair quality of life, nutritional status, and overall disease management.

Understanding the relationship between scleroderma and delayed gastric emptying is essential for patients, caregivers, and healthcare providers alike. Early recognition and appropriate treatment can reduce complications and improve daily functioning.

Understanding Scleroderma

Scleroderma, which literally means “hard skin,” involves abnormal collagen production leading to thickened and fibrotic tissues. It exists in two primary forms:

- Localized scleroderma, which mainly affects the skin.

- Systemic sclerosis, which involves internal organs such as the lungs, heart, kidneys, and gastrointestinal tract.

In systemic sclerosis, the gastrointestinal system is one of the most frequently affected organ systems. In fact, up to 90% of patients experience some degree of GI involvement during the course of the disease.

The digestive tract is a complex muscular system that relies on coordinated contractions to move food from the mouth to the stomach and through the intestines. In scleroderma, fibrosis and nerve dysfunction disrupt these coordinated movements, leading to motility disorders—including delayed gastric emptying.

What Is Delayed Gastric Emptying?

Delayed gastric emptying, or gastroparesis, is a condition in which the stomach takes longer than normal to empty its contents into the small intestine. Importantly, this delay occurs without a mechanical obstruction. Instead, the problem lies in impaired stomach muscle contractions and nerve signaling.

Under normal circumstances, food enters the stomach and is churned and mixed with digestive enzymes. Rhythmic muscular contractions push partially digested food into the small intestine at a controlled pace. When gastric emptying is delayed, food remains in the stomach for prolonged periods, leading to symptoms such as:

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Early satiety (feeling full quickly)

- Bloating

- Abdominal discomfort

- Loss of appetite

- Weight loss

In patients with scleroderma, delayed gastric emptying can develop gradually and may worsen over time as fibrosis progresses.

How Scleroderma Causes Delayed Gastric Emptying

The connection between scleroderma and gastroparesis lies in three major mechanisms:

1. Smooth Muscle Fibrosis

The stomach wall contains layers of smooth muscle responsible for contractions. In systemic sclerosis, excessive collagen deposition replaces normal muscle tissue with fibrotic tissue. This stiffening reduces the stomach’s ability to contract effectively, slowing food movement.

2. Neuropathy (Nerve Dysfunction)

The autonomic nervous system controls involuntary digestive processes. Scleroderma can damage these nerves, interfering with signals that regulate gastric motility. Without proper coordination between nerves and muscles, stomach contractions become weak or disorganized.

3. Vascular Abnormalities

Scleroderma also affects small blood vessels, reducing blood flow to tissues. Chronic ischemia (insufficient blood supply) may contribute to muscle and nerve damage within the stomach, further impairing gastric function.

The combination of fibrosis, nerve injury, and vascular compromise leads to progressive motility dysfunction.

Symptoms and Clinical Presentation

Patients with scleroderma-related delayed gastric emptying may experience a range of symptoms that vary in severity. Early symptoms are often subtle and may be mistaken for acid reflux or indigestion.

Common symptoms include:

- Persistent nausea

- Vomiting of undigested food hours after eating

- Early fullness after small meals

- Upper abdominal pain or discomfort

- Bloating

- Unintentional weight loss

- Malnutrition

- Worsening gastroesophageal reflux

Symptoms may fluctuate but often worsen as systemic disease progresses. Some patients develop severe malnutrition due to chronic inability to tolerate adequate oral intake.

Diagnosis

Diagnosing delayed gastric emptying in patients with scleroderma involves a combination of symptom evaluation and objective testing.

Clinical Evaluation

A healthcare provider will assess:

- Symptom pattern and duration

- Weight changes

- Nutritional status

- Medication use

- Other GI symptoms

Because many conditions can mimic gastroparesis, mechanical obstruction must first be ruled out.

Gastric Emptying Study

The gold standard diagnostic test is a gastric emptying scintigraphy study. During this test:

- The patient consumes a small meal containing a safe radioactive marker.

- Imaging tracks how quickly the stomach empties.

- Delayed retention of food at specified time intervals confirms gastroparesis.

Other diagnostic tools may include:

- Upper endoscopy

- Breath tests

- Wireless motility capsule studies

Early diagnosis is critical to prevent complications such as dehydration, severe malnutrition, or bezoar formation (hardened food masses in the stomach).

Complications

Delayed gastric emptying in scleroderma can lead to several serious complications:

Malnutrition

Inadequate calorie and nutrient intake can result in weight loss, muscle wasting, vitamin deficiencies, and weakened immunity.

Dehydration

Frequent vomiting may cause fluid imbalance and electrolyte disturbances.

Bezoars

Undigested food can accumulate and harden, forming masses that further obstruct gastric emptying.

Aspiration

Vomiting and reflux increase the risk of food or stomach contents entering the lungs.

Worsening Reflux

Scleroderma commonly causes lower esophageal sphincter dysfunction. When gastric emptying is delayed, increased stomach pressure can worsen acid reflux and esophageal damage.

These complications highlight the importance of proactive management.

Treatment Strategies

Managing delayed gastric emptying in scleroderma requires a comprehensive, multidisciplinary approach. Treatment focuses on symptom control, nutritional support, and addressing underlying motility dysfunction.

1. Dietary Modifications

Dietary changes are often the first step in management.

Recommendations include:

- Eating small, frequent meals

- Choosing low-fat foods (fat slows gastric emptying)

- Reducing high-fiber foods (which can form bezoars)

- Opting for soft or pureed foods

- Drinking liquids between meals rather than with meals

Liquid nutrition may be better tolerated than solid foods because liquids empty from the stomach more easily.

In severe cases, nutritional supplements or enteral feeding (via feeding tube) may be required.

2. Medications

Several medications may improve gastric motility or relieve symptoms:

Prokinetic Agents

These stimulate stomach contractions.

- Metoclopramide

- Erythromycin

- Domperidone (in certain countries)

While helpful, these medications may have side effects and must be monitored carefully.

Antiemetics

Used to control nausea and vomiting.

- Ondansetron

- Promethazine

Acid Suppression Therapy

Because reflux often coexists, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) may be prescribed.

Medication regimens are individualized based on symptom severity and tolerance.

3. Advanced Therapies

In refractory cases, additional interventions may be considered:

Gastric Electrical Stimulation

A surgically implanted device delivers electrical impulses to stimulate stomach contractions. This may reduce nausea and vomiting in selected patients.

Feeding Tubes

If oral intake is inadequate, jejunal feeding tubes may provide nutrition directly to the small intestine, bypassing the stomach.

Parenteral Nutrition

In extreme cases, intravenous nutrition (TPN) may be necessary, though it carries significant risks and is typically reserved for severe cases.

Managing Scleroderma Systemically

Because delayed gastric emptying is part of a broader autoimmune process, treating systemic sclerosis itself is also important. Immunosuppressive therapies may slow disease progression, although they do not always reverse established fibrosis.

Regular monitoring by rheumatologists, gastroenterologists, and nutrition specialists improves outcomes.

Psychological and Quality of Life Considerations

Chronic nausea, vomiting, and dietary restrictions can significantly impact mental health. Patients may experience:

- Anxiety around eating

- Social withdrawal

- Depression

- Fear of weight loss or choking

Supportive care, counseling, and patient education are essential components of treatment. Support groups for individuals with systemic sclerosis can also provide emotional reassurance and practical advice.

Prognosis

The severity of delayed gastric emptying in scleroderma varies widely. Some patients experience mild symptoms manageable with diet and medication. Others develop progressive motility failure requiring advanced nutritional support.

Unlike diabetic gastroparesis, scleroderma-related motility dysfunction is often progressive because it stems from structural tissue changes rather than purely metabolic dysfunction.

Early detection and proactive management can significantly reduce complications and improve long-term outcomes.

Research and Future Directions

Ongoing research aims to better understand:

- The molecular mechanisms driving fibrosis

- Early biomarkers of GI involvement

- Novel antifibrotic therapies

- Improved prokinetic medications with fewer side effects

Emerging therapies targeting immune pathways and fibrotic signaling may eventually help prevent or slow gastrointestinal involvement in systemic sclerosis.

Additionally, advances in motility testing and imaging may allow earlier identification of gastric dysfunction before severe symptoms develop.

Living With Scleroderma and Delayed Gastric Emptying

For patients, daily life may require adaptation. Practical strategies include:

- Keeping a symptom diary

- Planning meals carefully

- Staying upright after eating

- Maintaining hydration

- Working closely with a dietitian

- Monitoring weight regularly

Individualized care plans are critical because each patient’s disease pattern differs.

Family members and caregivers also play an important role in supporting nutritional management and recognizing warning signs such as persistent vomiting or rapid weight loss.

Conclusion

Scleroderma is far more than a skin disease—it is a systemic condition that frequently affects the gastrointestinal tract. Delayed gastric emptying represents one of its most challenging digestive complications. Caused by smooth muscle fibrosis, nerve damage, and vascular abnormalities, gastroparesis can significantly impair nutrition, comfort, and quality of life.

Fortunately, early recognition and a comprehensive treatment approach—including dietary modifications, medications, and supportive care—can improve symptoms and reduce complications. Multidisciplinary management is essential, involving rheumatologists, gastroenterologists, nutritionists, and mental health professionals.

As research continues to uncover new therapeutic targets, the future may hold improved options for preventing and treating gastrointestinal involvement in systemic sclerosis. Until then, patient education, early diagnosis, and individualized care remain the cornerstones of managing scleroderma-related delayed gastric emptying.

With proper support and medical guidance, many individuals can achieve better symptom control and maintain meaningful quality of life despite this complex condition.