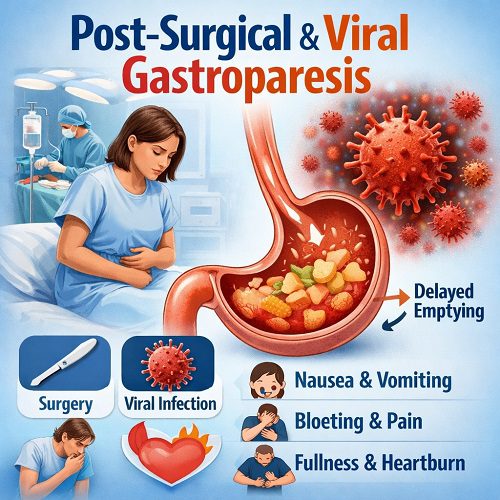

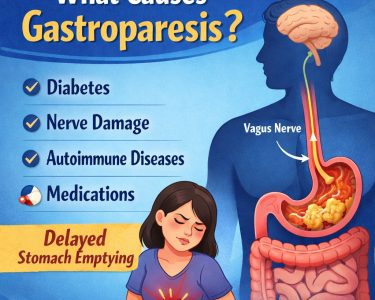

Gastroparesis is a chronic motility disorder in which the stomach empties food into the small intestine more slowly than normal, without a mechanical obstruction blocking the passage. The term literally means “stomach paralysis,” but in reality, the condition represents a spectrum of impaired gastric motility rather than complete paralysis. Among its various causes, post-surgical gastroparesis and viral (post-infectious) gastroparesis are two important yet often underrecognized forms. Understanding how and why they occur, how they present, and how they are treated is essential for both patients and clinicians.

Understanding Normal Gastric Emptying

To appreciate gastroparesis, it helps to understand how the stomach normally functions. After food is swallowed, the stomach performs several coordinated tasks:

- Storage: The upper part of the stomach (fundus) relaxes to accommodate incoming food.

- Grinding: The lower part (antrum) contracts rhythmically to break food into small particles.

- Regulated emptying: The pylorus (a muscular valve) opens in a controlled manner to allow properly processed food to pass into the duodenum.

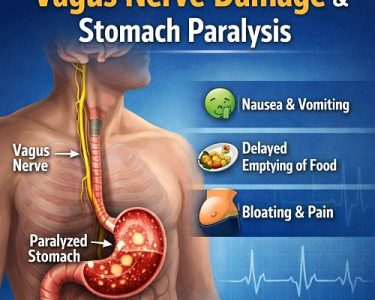

This process depends on intricate communication between smooth muscle, the enteric nervous system, and the vagus nerve—a major nerve connecting the brain to digestive organs. Any disruption to this coordinated system can delay gastric emptying.

What Is Post-Surgical Gastroparesis?

Post-surgical gastroparesis (PSG) refers to delayed gastric emptying that develops after surgery involving the stomach, esophagus, pancreas, or surrounding structures. It is most commonly associated with procedures that may inadvertently damage the vagus nerve or alter the stomach’s anatomy.

Common Surgeries Associated with PSG

Post-surgical gastroparesis has been reported after:

- Nissen fundoplication

- Gastrectomy

- Esophagectomy

- Pancreaticoduodenectomy

- Bariatric procedures such as gastric bypass

Although some degree of delayed emptying is common immediately after abdominal surgery, true post-surgical gastroparesis persists beyond the expected recovery period.

Mechanisms Behind Post-Surgical Gastroparesis

There are several mechanisms by which surgery can impair gastric motility:

- Vagal Nerve Injury:

The vagus nerve plays a central role in stimulating stomach contractions. Accidental damage during surgery can disrupt motor signaling, leading to reduced antral contractions and impaired pyloric relaxation. - Anatomic Alterations:

Resection or reconstruction of the stomach may alter its natural geometry and motility patterns. - Pyloric Dysfunction:

Scarring or altered innervation of the pylorus can prevent coordinated emptying. - Inflammation and Edema:

Temporary postoperative swelling may delay gastric emptying, though this typically resolves.

In many cases, post-surgical gastroparesis develops within weeks to months after the operation.

What Is Viral (Post-Infectious) Gastroparesis?

Viral gastroparesis, also known as post-infectious gastroparesis, occurs after an acute viral illness—often one involving gastrointestinal or systemic symptoms such as fever, nausea, and diarrhea.

Patients typically report a “stomach bug” or flu-like illness, followed by persistent nausea, early satiety, bloating, and vomiting that does not resolve after the infection clears.

Viruses Implicated

While the specific virus is not always identified, associations have been reported with:

- Norovirus

- Rotavirus

- Epstein-Barr virus

- Cytomegalovirus

The prevailing theory is that viral infections can trigger inflammation of the enteric nervous system, including the vagus nerve, leading to temporary or prolonged dysmotility.

Mechanisms of Viral Gastroparesis

- Autonomic Neuropathy:

Viral inflammation may damage autonomic nerves that regulate gastric motility. - Immune-Mediated Injury:

The immune response to infection may inadvertently injure interstitial cells of Cajal (the stomach’s pacemaker cells). - Myopathic Effects:

Inflammation may impair smooth muscle contractility.

Unlike post-surgical gastroparesis, viral gastroparesis often has a better prognosis, with many cases improving gradually over months.

Symptoms of Post-Surgical & Viral Gastroparesis

Although the causes differ, the symptoms are largely similar:

- Persistent nausea

- Vomiting (often of undigested food hours after eating)

- Early satiety (feeling full quickly)

- Postprandial bloating

- Abdominal discomfort

- Weight loss

- Malnutrition in severe cases

In post-surgical cases, symptoms may begin shortly after the procedure. In viral cases, symptoms typically follow an acute illness.

Diagnosis

Gastroparesis is diagnosed when three criteria are met:

- Typical symptoms

- Objective evidence of delayed gastric emptying

- No mechanical obstruction

Diagnostic Tests

- Gastric Emptying Scintigraphy (GES):

The gold standard test measures how long it takes for a radiolabeled meal to leave the stomach. - Upper Endoscopy:

Helps rule out structural obstruction. - Wireless Motility Capsule:

Evaluates transit times throughout the GI tract. - Breath Testing:

Non-invasive assessment of gastric emptying.

In post-surgical patients, imaging may also assess anatomic integrity. In viral cases, a recent infection history is often key to diagnosis.

Treatment Approaches

Management focuses on symptom control, nutritional support, and improving gastric emptying.

1. Dietary Modifications

Dietary therapy is foundational:

- Small, frequent meals

- Low-fat foods (fat slows gastric emptying)

- Low-fiber foods (fiber can form bezoars)

- Liquid or pureed meals, which empty more easily

In severe cases, jejunal feeding tubes may be necessary.

2. Medications

Prokinetics (stimulate motility):

- Metoclopramide

- Erythromycin

- Domperidone (in certain regions)

Antiemetics (control nausea):

- Ondansetron

- Promethazine

Response varies. Viral gastroparesis often responds better over time.

3. Endoscopic & Surgical Interventions

For refractory cases:

- Pyloric botulinum toxin injection

- Gastric electrical stimulation

- Surgical pyloroplasty

Gastric electrical stimulation devices are sometimes used in severe cases, particularly when vomiting is the dominant symptom.

Prognosis

Post-Surgical Gastroparesis

The course varies:

- Some patients improve within months.

- Others experience chronic symptoms.

- Prognosis depends on the extent of nerve damage.

If vagal injury is partial, compensatory mechanisms may restore function over time.

Viral Gastroparesis

The outlook is generally more favorable:

- Many patients recover partially or fully within 6–12 months.

- Some develop chronic symptoms.

- Children and young adults often have better recovery rates.

Early supportive care and nutritional management improve outcomes.

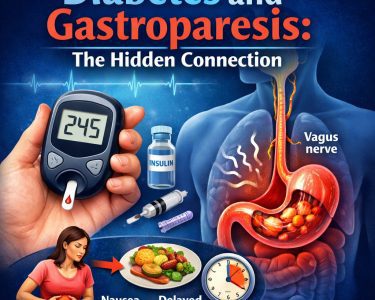

Complications

If untreated or severe, gastroparesis can lead to:

- Malnutrition

- Dehydration

- Electrolyte imbalance

- Bezoar formation (hardened food masses)

- Poor glycemic control in diabetic patients

Psychological distress is also common due to chronic nausea and lifestyle disruption.

Emerging Therapies & Research

Research is ongoing to better understand gastroparesis pathophysiology.

Areas of interest include:

- Immune-modulating therapies for post-infectious cases

- Stem cell approaches targeting interstitial cells of Cajal

- Improved gastric pacing devices

- Novel prokinetic agents

As understanding of neurogastroenterology advances, more targeted therapies may emerge.

Living with Gastroparesis

Patients often benefit from multidisciplinary care involving:

- Gastroenterologists

- Dietitians

- Surgeons (if needed)

- Mental health professionals

Support groups and patient education are essential for improving quality of life. Chronic nausea and dietary restriction can significantly impact emotional well-being.

Conclusion

Post-surgical and viral gastroparesis represent two distinct pathways leading to the same functional outcome: impaired gastric emptying. In post-surgical cases, mechanical or neural injury—especially involving the vagus nerve—is typically responsible. In viral cases, inflammation and immune-mediated nerve dysfunction often play central roles.

While symptoms overlap, prognosis differs. Viral gastroparesis frequently improves over time, whereas post-surgical gastroparesis may persist depending on the degree of nerve damage.

Early diagnosis, dietary modification, appropriate medications, and supportive care are key to improving outcomes. As research continues to unravel the complex neurobiology of gastric motility, more effective and individualized treatments may soon become available.

Understanding these conditions not only helps clinicians tailor therapy but also empowers patients navigating the challenging experience of chronic digestive dysfunction.