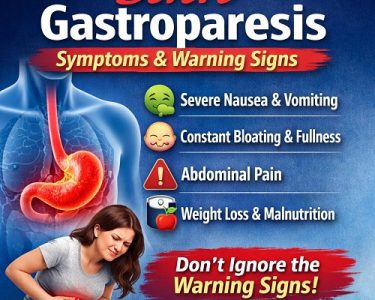

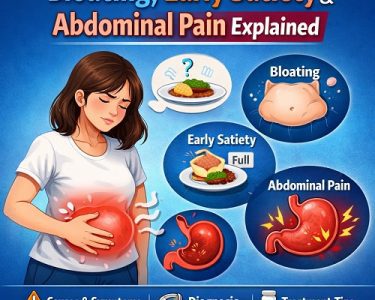

Gastroparesis is a chronic digestive disorder that literally means “stomach paralysis.” The term comes from “gastro” (stomach) and “paresis” (partial paralysis). In people with gastroparesis, the stomach’s ability to move food into the small intestine is slowed down or disrupted, even though there is no physical blockage. This delay in gastric emptying can lead to symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, bloating, abdominal pain, early satiety (feeling full quickly), and fluctuations in blood sugar levels.

While the symptoms can be distressing and sometimes debilitating, understanding what causes gastroparesis is key to managing it effectively. The condition is complex and often multifactorial, meaning that several different mechanisms and underlying diseases can contribute. This article explores in depth the main causes of gastroparesis, how they affect stomach function, and why the condition develops in certain individuals.

How the Stomach Normally Works

To understand what causes gastroparesis, it is helpful to know how a healthy stomach functions. After food is swallowed, it travels down the esophagus and enters the stomach. The stomach has three major jobs:

- Storage: It temporarily holds food.

- Mechanical digestion: It churns and grinds food into smaller particles.

- Controlled emptying: It gradually releases partially digested food into the small intestine.

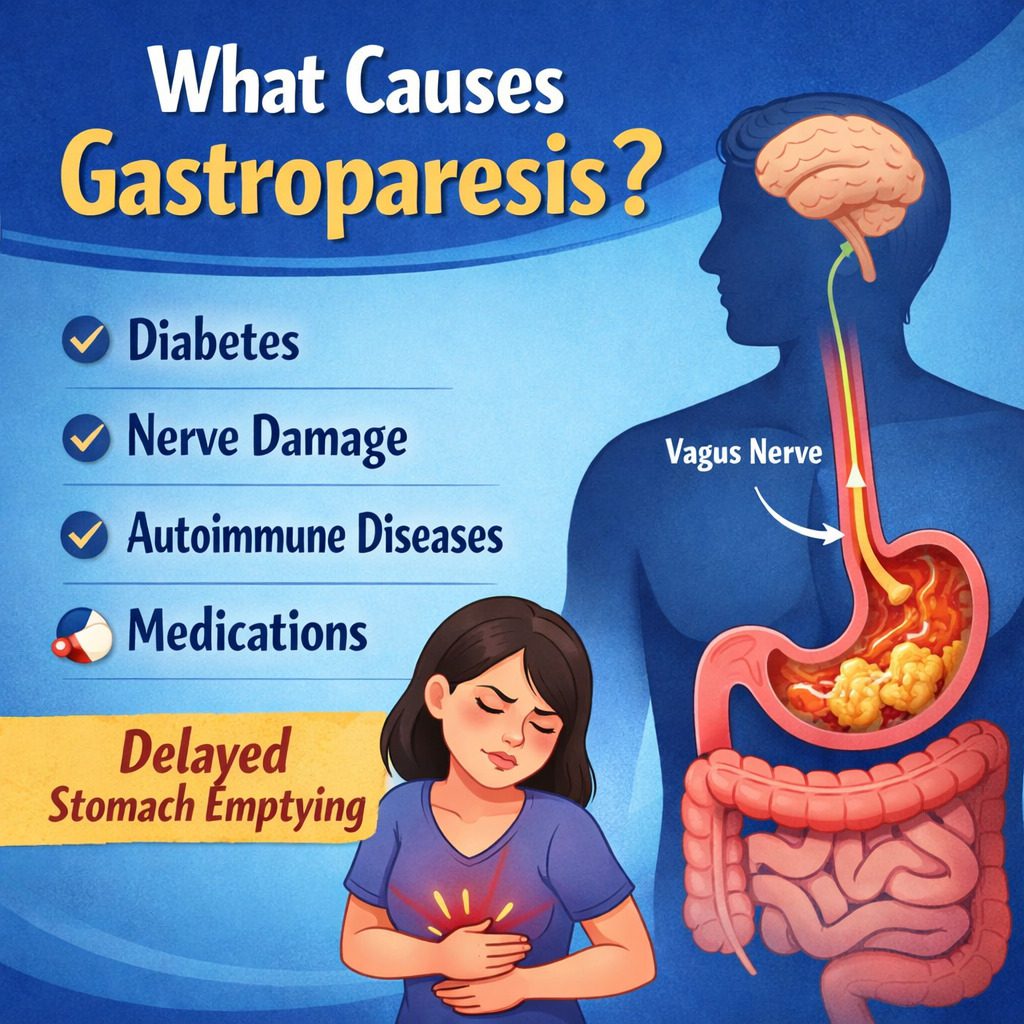

These tasks depend on coordinated muscle contractions controlled by the nervous system. A key player in this process is the vagus nerve, which sends signals from the brain to the stomach muscles, telling them when and how strongly to contract. Specialized pacemaker cells in the stomach wall, known as interstitial cells of Cajal, also help regulate rhythmic contractions.

When any part of this finely tuned system is damaged or disrupted—whether the nerves, muscles, or pacemaker cells—the stomach may empty too slowly. This delay is what defines gastroparesis.

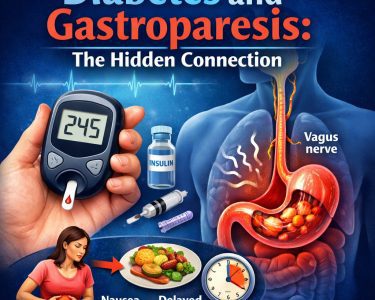

1. Diabetes: The Most Common Cause

One of the most well-known and common causes of gastroparesis is diabetes, particularly long-standing or poorly controlled diabetes. Both type 1 and type 2 diabetes can lead to this condition.

High blood sugar levels over time can damage nerves throughout the body, a complication known as diabetic neuropathy. When this damage affects the vagus nerve, the stomach muscles may no longer receive proper signals to contract. As a result, food remains in the stomach longer than normal.

This creates a vicious cycle. Delayed stomach emptying makes blood sugar levels more unpredictable because food absorption becomes irregular. In turn, fluctuating blood sugar can further impair stomach motility.

In people with diabetes, gastroparesis often develops gradually. It may begin with mild symptoms such as bloating or early fullness and progress over time. Strict blood sugar control is one of the most important strategies for preventing or slowing its progression.

2. Surgical Complications

Another significant cause of gastroparesis is injury to the vagus nerve during surgery. Operations involving the stomach, esophagus, pancreas, or upper small intestine can sometimes disrupt the nerves that control gastric motility.

Procedures such as gastric bypass, fundoplication (used to treat acid reflux), or surgeries for ulcers and tumors may inadvertently damage the vagus nerve. When this happens, the communication between the brain and stomach is impaired, leading to delayed gastric emptying.

In some cases, gastroparesis following surgery may improve over time if the nerve partially recovers. In others, it may become a long-term complication requiring dietary changes and medication.

3. Viral Infections

Certain viral infections are believed to trigger gastroparesis, particularly in cases where symptoms begin suddenly after a bout of illness. This is sometimes referred to as post-viral gastroparesis.

Viruses can cause inflammation of the nerves that regulate stomach function. Even after the infection resolves, the damage to the vagus nerve or the stomach’s pacemaker cells may persist. Common viral triggers include norovirus and rotavirus, although many different viruses may be involved.

Post-viral gastroparesis can affect otherwise healthy individuals. In some cases, symptoms gradually improve over months or years as nerve function recovers. In others, the condition may become chronic.

4. Autoimmune Disorders

Autoimmune diseases occur when the immune system mistakenly attacks the body’s own tissues. In some individuals, the immune system targets components of the nervous system that regulate digestion.

Conditions such as lupus, scleroderma, and autoimmune autonomic neuropathy have been linked to gastroparesis. In these cases, the body’s immune response damages the nerves or muscles involved in gastric motility.

For example, in scleroderma, connective tissue changes can stiffen and weaken the muscles of the digestive tract. This reduces the stomach’s ability to contract effectively, slowing emptying.

Autoimmune-related gastroparesis may coexist with other symptoms, depending on the underlying disease, such as joint pain, skin changes, or systemic inflammation.

5. Neurological Disorders

Because stomach movement depends heavily on the nervous system, neurological conditions can also cause gastroparesis. Diseases that affect the brain, spinal cord, or peripheral nerves may disrupt the signals needed for coordinated gastric contractions.

Conditions such as Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, and stroke have all been associated with delayed gastric emptying. In Parkinson’s disease, for example, degeneration of nerve cells affects not only movement but also autonomic functions like digestion.

Neurological causes of gastroparesis may present alongside other symptoms, such as tremors, muscle weakness, or balance problems, depending on the specific disorder.

6. Medications

Certain medications can slow stomach emptying as a side effect. In some cases, this effect is mild and temporary. In others, especially with long-term use, it may contribute to clinically significant gastroparesis.

Drugs that can delay gastric emptying include:

- Opioid pain medications

- Anticholinergic drugs

- Some antidepressants

- Calcium channel blockers

- GLP-1 receptor agonists used for diabetes and weight loss

Opioids, in particular, reduce gut motility by acting on receptors in the digestive tract. When possible, adjusting the dosage or switching medications may improve symptoms.

7. Connective Tissue Disorders

Certain connective tissue diseases, such as scleroderma and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, can impair the structure and function of the stomach wall.

In scleroderma, excess collagen deposits can stiffen digestive organs, reducing their ability to contract. In Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, abnormal connective tissue may affect the integrity and coordination of smooth muscle contractions.

These structural changes interfere with normal gastric motility and may contribute to chronic digestive symptoms, including gastroparesis.

8. Hormonal and Metabolic Disorders

Hormonal imbalances can also affect stomach motility. Thyroid disorders, particularly hypothyroidism (an underactive thyroid), may slow metabolic processes and reduce gastrointestinal movement.

Other metabolic disturbances, such as electrolyte imbalances, can interfere with muscle contractions. Low levels of potassium, magnesium, or calcium may impair the stomach’s ability to function properly.

In many of these cases, treating the underlying hormonal or metabolic issue can improve gastric emptying.

9. Idiopathic Gastroparesis

In a significant number of cases, no clear cause can be identified. This is referred to as idiopathic gastroparesis. “Idiopathic” simply means that the origin is unknown.

Idiopathic cases may account for up to one-third of all gastroparesis diagnoses. Some researchers believe that many of these cases may actually result from undiagnosed viral infections or subtle autoimmune processes.

Even without a known cause, the impact on quality of life can be substantial. Ongoing research aims to better understand the underlying mechanisms of idiopathic gastroparesis.

10. Damage to the Stomach’s Pacemaker Cells

The interstitial cells of Cajal play a crucial role in coordinating rhythmic contractions of the stomach. These cells act as electrical pacemakers, generating slow waves that stimulate muscle movement.

In some individuals with gastroparesis, these pacemaker cells are reduced in number or function abnormally. This disruption can occur due to diabetes, inflammation, autoimmune processes, or unknown factors.

Without proper pacemaker activity, the stomach’s contractions become weak, uncoordinated, or absent, resulting in delayed emptying.

11. Psychological Stress and Functional Disorders

Although gastroparesis is a physical condition, psychological stress can influence gastrointestinal function. The brain and gut are closely connected through the gut-brain axis.

Chronic stress, anxiety, and depression may alter nerve signaling and exacerbate digestive symptoms. While stress alone does not typically cause structural gastroparesis, it can worsen symptoms or contribute to functional motility disorders that resemble gastroparesis.

Distinguishing between true gastroparesis and functional dyspepsia sometimes requires specialized testing, such as gastric emptying studies.

12. Cancer and Radiation Therapy

Certain cancers, particularly those affecting the stomach or pancreas, may impair gastric motility. Tumors can interfere with nerve function or muscle integrity.

Radiation therapy to the abdominal region may also damage nerves and tissues involved in stomach contractions. This can lead to delayed gastric emptying either during or after cancer treatment.

In these cases, managing gastroparesis becomes part of the broader cancer care plan.

Why Some People Develop Gastroparesis and Others Do Not

Not everyone with diabetes, surgery, or viral infection develops gastroparesis. Researchers believe that genetic predisposition, immune responses, severity and duration of disease, and lifestyle factors all play roles.

The interplay between nerves, muscles, immune cells, and pacemaker cells in the stomach is highly complex. Small variations in these systems may influence an individual’s vulnerability to motility disorders.

Conclusion

Gastroparesis is a multifaceted condition with a wide range of potential causes. The most common cause is diabetes-related nerve damage, but surgical injury, viral infections, autoimmune disorders, neurological diseases, medications, connective tissue disorders, and hormonal imbalances can all contribute. In many cases, the cause remains unknown.

At its core, gastroparesis results from disrupted communication between the brain, nerves, and stomach muscles. Whether due to nerve injury, muscle dysfunction, pacemaker cell loss, or systemic disease, the outcome is the same: delayed gastric emptying without a physical blockage.

Understanding the underlying cause is essential because treatment strategies often depend on addressing the root problem. For example, improving blood sugar control in diabetes, adjusting medications, or treating an autoimmune disorder may reduce symptoms.

Although gastroparesis can be challenging to manage, advances in research continue to improve our understanding of its causes and potential therapies. Greater awareness and early diagnosis can help individuals receive appropriate care and improve their quality of life.